A Land at the Crossroads: Myanmar’s Fraught Friendships

The Rohingya-crisis has attracted the attention of the international community for some years. Yet, the latter has failed to act on a situation which has long been suspected to qualify as ethnic cleansing or even genocide, and which has been described as one of the ‘most prolific slaughterhouses of our times’ by the former Commissioner for Human Rights of the United Nations (UN), Zaid Ra’ad Al Hussein (Al Hussein 2018). Thus, Gambia’s move to sue Myanmar with the support of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation (OIC) at the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in late 2019 was welcomed by NGOs and human rights groups across the world. The lawsuit itself will likely drag on for years, however, the ICJ’s unanimous decision in January 2020 to order preliminary measures – instructing Myanmar to prevent further acts of genocide and abstain from destroying evidence of past genocidal acts – was hailed as a victory of human rights and a step towards justice (Win 2020, Oxfam 2020).

For the Western world, and for the EU in particular, the lawsuit constitutes a dilemma. Can Europe, born itself out of the horrors of the ‘crime of crimes’ and traditionally priding itself of its role in the world as a normative stronghold, simply close its eyes to an alleged genocide occurring elsewhere on the globe? Why is it that Europe has, apart from a statement urging Myanmar to implement the World Court’s order and vague threats to strip Myanmar of its ‘Everything but Arms’ (EBA) trade benefits, not expressed more concern for the situation?

The reasons for this indecisiveness are sensible. In recent years, Myanmar’s image vis-à-vis the Western world has increasingly deteriorated. In particular Aung San Suu Kyi, Myanmar’s head of state and Nobel Peace Prize laureate, has fallen from grace for her inaction and most recent defense of the crimes committed against the Rohingya. This has led to a sharp decline of Western tourists and investors fearing for their reputation (Ballard 2020) and compelled Myanmar – a country in dire need of financial resources – to move closer into China’s sphere of influence. China, fashioning itself in terms of its ‘fraternal bond’ (Pauk-phaw) to Myanmar, gladly grasps this opportunity: Myanmar’s rich endowment in natural resources, as well as its geostrategic position at the shore of the Indian Ocean make it a high-priority focus of Chinese strategists (Ott 2020). In this vein, Myanmar’s government has signed more than 30 MoUs (Memorandums of Understanding) with Chinese President Xi Jinping during the latter’s ‘historic’ visit earlier this year. It resulted inter alia in agreements for increased cooperation on various large-scale infrastructure projects – many of which are to be built in active conflict or contested territories (Lwin 2020).

China openly collaborates with the Tatmadaw, Myanmar’s military, which has a vast record of human rights violations and now stands accused for committing genocide while at the same time Myanmar’s government-opposing Ethnic Armed Organizations are provenly supplied with Chinese weapons (Tiezzi 2019, Inkey 2018). It is mere speculation if this constitutes a conscious ‘divide-and-conquer’ strategy aiming at keeping Myanmar weak and hence controllable, as claimed by some authors (Zaw 2020). However, what is clear is that such dual strategies do not aid the peace process of a state that has the record of being host to the most protracted civil war of our times.

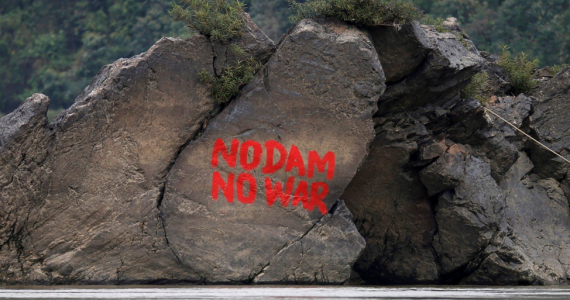

Furthermore, China’s unscrupulous pursuance of its economic interests in Myanmar might have fatal consequences for the fragile democratization process that was set in motion about 10 years ago. Having been under stern authoritarian rule since its independence from Britain in 1947, a gradual reform process has set off in Myanmar from 2011 onwards, with elections held in 2015 that were largely considered fair and free by international observers (Carter Center 2016). China’s ambitions in Myanmar have always been viewed with skepticism by the Burmese public, not least since several of the planned Chinese-sponsored mega-projects require the relocation of entire villages and potentially entail massive environmental damage. In the wake of Myanmar’s democratization, therefore, the consecutive governments of Thein Sein and later Suu Kyi have had to walk a fine line between appeasing the powerful neighbor while at the same time securing the support of the people. When the international community lifted its sanctions in the years following 2011 and replaced them with generous trade benefits, FDI and other types of financial aid, Myanmar felt confident enough to halt the most contentious Chinese investment projects – most notably that of the infamous Myitsone dam – due to the general public’s animosity towards them (Slow 2019). With Myanmar’s increasing dependence on China, however, the balance may shift back in favor of the latter. A recently published report by an ethnic rights group in Eastern Myanmar may serve as evidence that such a shift is already taking place. The report, named ‘Gambling Away Our Lands’, details the construction of a Chinese-sponsored mega project including an airport, casinos and apartment blocks on territories inhabited by ethnic Karen communities. The report not only accuses relevant authorities of excluding local communities from the planning process, but also of seizing their lands and depriving them of their livelihoods. Incomes generated from construction and maintenance of the project could in principle have compensated the loss of incomes generated from seized lands; however, jobs on the site were given exclusively to Chinese nationals (KPSN 2020).

The potential of processes like the one described above to create grievances and fuel conflict is obvious. Any measure by the EU that entails Myanmar’s further alienation from the Western world might increase the country’s dependence on China and may therefore have detrimental effects on its democratic reforms and peace process. The consequences will be borne by Myanmar’s civilian population, which has little to do with the genocide allegations. This may explain Europe’s seeming disinterest in condemning the atrocities against the Rohingya in word or deed. However, it is questionable whether Europe’s wait-and-see attitude is a wise tactic for a political actor that repeatedly stresses its will to increase its relevance as a global player (see Mogherini 2019).

Europe’s indecisiveness with regard to its handling of the Myanmar case is a symptom of its seeming insecurity about its own role in world politics. Having recently turned away from a foreign policy approach centered around the diffusion of values and morality, the 2016 Global Strategy embraces a new policy paradigm with the idea of ‘principled pragmatism’ at its heart, about which there is still much confusion (e.g. Juncos 2017; Wagner & Anholt 2016). In the face of much criticism regarding the abandonment of a human rights-centered approach for the sake of an ill-defined interest, the previous EU minister for Foreign Affairs, Frederica Mogherini, still established rhetorical links between self-interest with value diffusion. In her 2019 speech at Oxford University, the terms ‘values’ and ‘interests’ are conjunctively referred to in no less than 5 sentences (Mogherini 2019).

The Myanmar case exemplifies, however, that the policy objectives of value diffusion and the defense of self-interest do not always alight as smoothly as suggested by EU ministers. Upholding economic and diplomatic ties even in the face of allegations of genocidal acts in a state with vast and largely untapped potential certainly constitutes a pragmatic approach, but involves ignoring the worst of all crimes, and therefore the betrayal of the EU’s core values. On the other hand, condemnation, imposition of sanctions or any other measure that would contribute to a further isolation of Myanmar from the West may involve pushing it into China’s embrace, facilitate the erosion of the nascent democracy, and ultimately contribute to the EU’s own marginalization in the context of a world increasingly governed by Realpolitik.

Sources

Al Hussein, Z.R. (2018). Opening statement by UN High Commissioner for Human Rights. 37th session of the Human Rights Council.

Ballard, B. (2020). The benefits (and risks) of investing in Myanmar. World Finance.

European Commission (2019). EU monitoring mission evaluates progress on human rights in Myanmar. Brussels.

European External Action Service (2020). Statement by the Spokesperson on the ICJ ruling on the case brought by The Gambia against Myanmar. European External Action Service.

Inkey, M. (2018). China’s Stake in the Myanmar Peace Process. The Diplomat.

Juncos, A. E. (2017). Resilience as the new EU foreign policy paradigm: a pragmatist turn?. European security, 26(1), 1-18.

KPSN (2020). Gambling Away Our Land. Naypyidaw’s “Battlefields to Casinos” Strategy in Shwe Kokko. Kesan Asia.

Lwin, N. (2020). Myanmar, China Sign Dozens of Deals on BRI Projects, Cooperation During Xi’s Visit. The Irrawaddy.

Mogherini, F. (2019). Speech by High Representative/Vice-President Frederica Mogherini on “The EU’s Role as a Global Player for Peace and Stability” at Oxford University. European External Action Service.

Ott, M.C. (2020). Myanmar in China’s embrace. Foreign Policy Research Institute.

Oxfam (2020). Oxfam reaction to International Court of Justice decision on Myanmar. Oxford International.

Slow, O. (2019). With China-Backed Myitsone Project, Aung San Suu Kyi is damned if she does…. South China Morning Post.

Tiezzi, S. (2019). China, Myanmar Extol ‘Eternal’ Friendship as Commander-in-Chief Visits Beijing. The Diplomat.

Wagner, W., & Anholt, R. (2016). Resilience as the EU Global Strategy’s new leitmotif: pragmatic, problematic or promising?. Contemporary security policy, 37(3), 414-430.

Win, K (2020). ICJ Ruling a Major Victory for Rohingya that the World Must Enforce. Burma Human Rights Network.

Zaw, A. (2020). An Unstable, Weak Myanmar: China’s Strategic Goal? The Irrawaddy.

Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of CISS or its members.

Anne Heckendorff

Anne Heckendorff is a recent graduate from Utrecht University and is currently working as an intern for an NGO in Myanmar.